| Series |

|---|

Day 17: 25 Insights in 25 Days 2019 New Year Marathon!

Should creatives feel threatened by the rise of Machine Learning?

Creativity makes us human. What is the place of AI in this area? If computers become too human, will we ultimately be reduced to little more than machines?

There is a lot of talk about how AI will impact the creative industries, from technological displacement of our jobs market, to creative computers. To really explore the extent to which AI can create art, we need to query how it’s done, by both humans and machines. We must also consider the most basic of questions:

- What is art?

- What is creativity?

From there, we can consider whether these definitions fit the current and projected abilities of computers.

Beyond the hype: the current science of Artificial Intelligence

AI is not new. The exact technology that we are using today has been around for decades. While used technology to augment our selves for millennia, as Richard Watson puts it, “the difference this time is ubiquity, scale, and impact.”

Artificial Intelligence was huge in the 1950’s. Marvin Minsky and Dean Edmonds built the first neural network machine, able to learn, the SNARC in 1951. IBM built a Machine Learning program to play checkers, in 1952.

In 1966 the first chatbot was demonstrated, called ELIZA. It matched user input to scripted responses, not too far removed from our more elegant counterpart today.

In the 70’s and 80’s, various more complex methodologies were developed for Neural Networks to make machine learning more sophisticated. While many people were working on this, the father of machine learning is considered to be Geoffrey Hinton. His method described in 1986 is the one that forms the basis of most ML algorithms described as “deep learning” from this point forward.

Even self-driving cars, which are being discussed as a new innovation today, are “vintage” technology. The first autonomous car was demonstrated in 1979 at Stanford. Then, in 1987 it was formally developed and deployed as a joint project between Mercedes, various researchers and the US Military. This later vehicle used the same technology as self-driving cars today.

The reason why all these innovations didn’t take off last century, and are suddenly a big deal now, is because today we finally have the resources to make them really good. Today’s computing power, combined with the vast training data of the Internet, allows computers to process, detect patterns, learn and perform at a level that’s actually useful and possible to commodify today.

Check out my previous primer on AI and ML for a bit more of an explainer on all of this. This quote from Stanford and Google’s Fei-Fei Li beautifully sums up today’s technology, often described as “idiot savant”

“the definition of today’s AI is a machine that can make a perfect chess move while the room is on fire”

I love this quote. It additionally describes how AI and humans’ strengths and weaknesses are opposite and complementary. This very nature of computers is the opposite of our nature as humans. Using machines as tools can powerfully augment our human abilities by reducing our weaknesses.

“Teaching a machine to deal with a logical problem such as playing chess is relatively easy. Teaching a robot kung-fu could be a maths problem.

But getting a machine to think about snow slowly falling or wind on the Welsh hills, or to be moved by poetry, is different.”

How does a computer create art?

Let’s look briefly at the current science. For a deeper dive, check out my explainer on AI/ML.

A lot of headlines today claim that computers are creating art and are set to replace creatives. That said, the World Development Report 2019 notes that in line with expert predictions on the impact of AI on the workforce, in both advanced and emerging economies, people with advanced cognitive and emotional skills are in greater demand.

The lucky few who can be involved in creative work of any sort will be the true elite of mankind, for they alone will do more than serve a machine.

-Isaac Asimov

Is learning to cook the same as being a chef?

Due to the decades-old technology of AI/ML, its basic simplicity and its inherent limitations, it’s easy to understand exactly how different computer programs create art. They essentially build a mash-up of work deemed “good” by previous humans. In other words, machine-learning itself is based on coming up with something that is “correct”. The correct result is reinforced by the approval of the programmer or operator.

IBM’s Chef Watson, for example, is an AI created as a marketing exercise in conjunction with a popular food magazine. It takes input of a selection of ingredients, and a style of cooking. It searches the magazine’s recipe archive, detects patterns which align with those ingredients and cuisine styles, and suggests recipes based on those patterns. It also pulls from a database of known flavor combinations which are considered palatable to most people. Since the computer program itself can’t taste, the human chef chooses which of the suggested ingredient combinations are actually a good idea and which are not.

But is that creative?

To answer that, we need to define creativity, and art, and decide whether it fits with what computers are doing?

The simplest argument is that if, by definition, an AI creates something original by taking massive amounts of data and finding common patterns, anything it generates would be derivative at best. But so is a lot of human-generated work.

One of the inherent limitations of AI is that anything unusual, any “outlier” generated would be discarded as “wrong”. Many argue that advancements in creativity are all about things that are new and different. Things which are truly considered creative are generally things that are out of the ordinary. Being extraordinary is what defines artists. One thing a computer can not do is break the rules that have been set for it.

What is art, and what makes something not art?

I have spent a lot of time working on this very question as part of my own research into the future of creative industries. There are many varied definitions out there already:

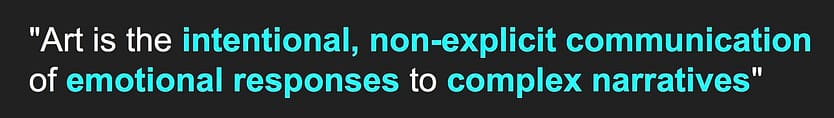

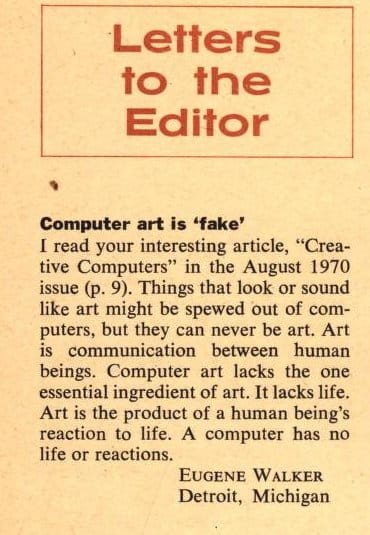

Below is my own definition of art. I’ve highlighted certain words, as I think they each need to be considered when determining whether something is, or is not, art. It is by using this definition that I do my own work in the field of examining cognitive/creative machines.

What is the difference between creating and being creative?

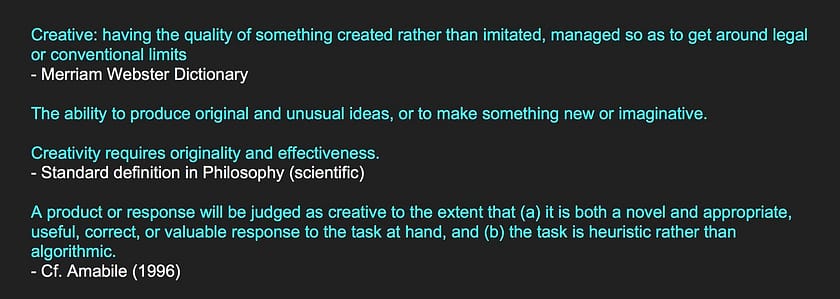

Similarly, we need to define creativity to determine whether a computer can be creative. At what point does a chair in a room go from being simply that, to being an installation at MOMA?

Again, there are a number of definitions. There is more consensus on the definition of creativity, in fact the US Patent Office also requires something to be “both a novel and appropriate, useful, correct, or valuable response to the task at hand” if it is to be deemed a creative work.

My personal favorite definition of creativity, because it’s the most creative, is this one:

Over the years I’ve been studying this, I have not yet settled on a concise definition of creativity. So far, I can say that these two statements are true:

The point at which “creating” turns into “being creative” occurs when the intention goes beyond the object, to the intention of the object to communicate something.

and:

Creativity requires intentionally breaking or diverging from pre-defined rules or instructions, to generate something unique or new, that also serves the intended purpose.

It’s important to note that it is widely agreed that in order to be “creative”, a work cannot be random. The work must be a novel solution to an intended purpose, that actually serves that purpose. Look back at many of the wacky examples of inventions, fashion, cuisine, music and classic art that are generated by computers. The uselessness of a large proportion of the outputs, due to lack of context or intention, may alone disqualify these AI from being defined as creative.

“Perceiving an emotion and experiencing an emotion are not one and the same.”

How do our brains make art?

We’ve covered how computers do it. How humans process creativity into creative output is something no scientist has defined. A review of the current research across psychology, neuroscience, anthropology and human biology offers only a few clues.

Art is an expression or communication of complex emotion. In the past three decades, scientists have identified and mapped the parts of the human brain responsible for the chemical transmitters and receptors associated with emotional response.

Humans are born hard-wired with four basic emotions:

- pleasantness

- unpleasantness

- arousal

- calmness.

Everything after that is learned based on experience. Every person is unique. We learn how to express and understand and make more complex ideas about emotion based on a combination of the physical introspection and the experience itself. But without the physical part, we only infer from the experience.

AI is said to learn as a baby does.

A baby learns emotions, starting with the four physically-linked feelings. It then learns complex ways of describing nuanced situational variations of these emotions by feedback. Because they are learned, emotions are also deeply linked to culture. They are not universal. This is why the scientific community has struggled to find much commonality in the mechanism of our brains’ response when we feel. Hundreds of studies have been performed trying to find consistency across human brain scans when feeling or expressing complex emotions, making art, or being creative. None have succeeded.

To date, studies have only shown cross-cultural similarities in the way humans express five basic feelings

Using facial cues, vocal cues and through MRI scans those which have been observed are:

- angry

- sad

- relieved

- joyful

- neutral

For example, people tend to smile when happy, and raise their voices when angry. This is the extent to which we have been able to train computers to perceive and perform emotional responses. We are a long way from even defining jealousy, fear or guilt.

Computers can read and imitate social cues associated with these less complex emotions. They cannot feel those emotions. An extremely complex line of code can only process a frown as an expression of displeasure, and respond appropriately.

Scientists have also done research on musicians and artists at work. Studies have shown that improvising music has led to deactivation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which plays a key role in such functions as planning, working memory, and abstract reasoning. Emotions, creativity and art, are inherently illogical.

The common narrative too often overestimates technology and underestimates society.

I can not emphasize this enough. It is essential to remember when considering any predictions or shocking headlines about technology. It is especially important to note when looking at technology’s role in art and creativity.

Why do we create and consume art? We do it for pleasure. Art is when we take an act beyond being utilitarian. Scientists are able to agree that when people are being creative, their brains show that they are responding with pleasure, in a way that can even become addictive.

Never underestimate what might happen when when something we do primarily for enjoyment (secondarily for purpose) is taken from us. Beyond any argument over whether a computer can, or will be creative, there is a greater question to pose. Would we ever want, or allow, computer-generated art to displace the indescribable feeling of a communication beyond words, of a unique set of complex emotions, between a creative and their audience?

Can computers be creative?

We have defined creativity, and we have defined art. We have explored the nature and mechanism of AI and how it creates output.

An AI can have intention, but it is not aware of that intention therefore: The programmer has the intention, not the AI.

A computer program will create novel and (sometimes) unique work, but it is rarely fit for purpose and requires a human to determine this.

While an algorithm may be able to process complex narratives, it can not have, understand nor communicate an emotional response. It has no awareness, no context and most importantly, no physical self through which it can experience senses.

That said, computers can create. The “idiot savant” has the advantage of being unrestrained by culture, experience or context. An AI can augment human creativity. The computer is the perfect chess move, human nature is the room that’s on fire. Together, AI and artists make a perfect team.

Part of my professional work requires me to make predictions about the future of our industry. I do this by examining the science, and the very nature of the posed question from many different positions. This tutorial should help you be more informed about creative computers. You are now armed with the ability to understand the possibilities, and limitations, that lie ahead in the tools afforded to us by AI.

![[In order to distinguish Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes from actual Brillo boxes, art can be defined as] embodied meaning. – Arthur C. Danto (1924–2013), American philosopher of art, What Art Is (2013) To evoke in oneself a feeling one has experienced, and…then, by means of movements, lines, colors, sounds or forms expressed in words, so to transmit that feeling—this is the activity of art. – Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910), Russian author, What is Art? (1890) Art has to move you and design does not, unless it's a good design for a bus. – David Hockney (1937–) British artist, to The Guardian on October 26, 1988 “Art is an expression of our thoughts, emotions, intuitions, and desires, but it is even more personal than that: it’s about sharing the way we experience the world, which for many is an extension of personality. It is the communication of intimate concepts that cannot be faithfully portrayed by words alone. And because words alone are not enough, we must find some other vehicle to carry our intent. But the content that we instill on or in our chosen media is not in itself the art. Art is to be found in how the media is used, the way in which the content is expressed.”](https://images.mixinglight.com/cb:sOVj.5c7e3/w:840/h:463/q:mauto/f:best/ig:avif/https://mixinglight.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/definitions-of-art-e1547085982199.jpg)